Work is now underway as the City of Peoria begins addressing its persistent Combined Sewer Overflow problem.

Last month, crews began installing permeable pavers and bump-out planters along roadways on the Near North side to start the 18-year CSO Control Project stemming from a 2020 consent decree negotiated with the U.S. Environmental Protection agency.

But what exactly is CSO and how will the control project resolve the issue? What kind of work will be done? How much will it cost, and will those costs be passed on to residents?

City engineer Andrea Klopfenstein speaks with WCBU reporter Joe Deacon to answer these questions and more. This transcript has been edited for clarity and brevity.

A lot of people in Peoria know about the Combined Sewer Overflow problem, but can you explain it for those who might not know what CSO is?

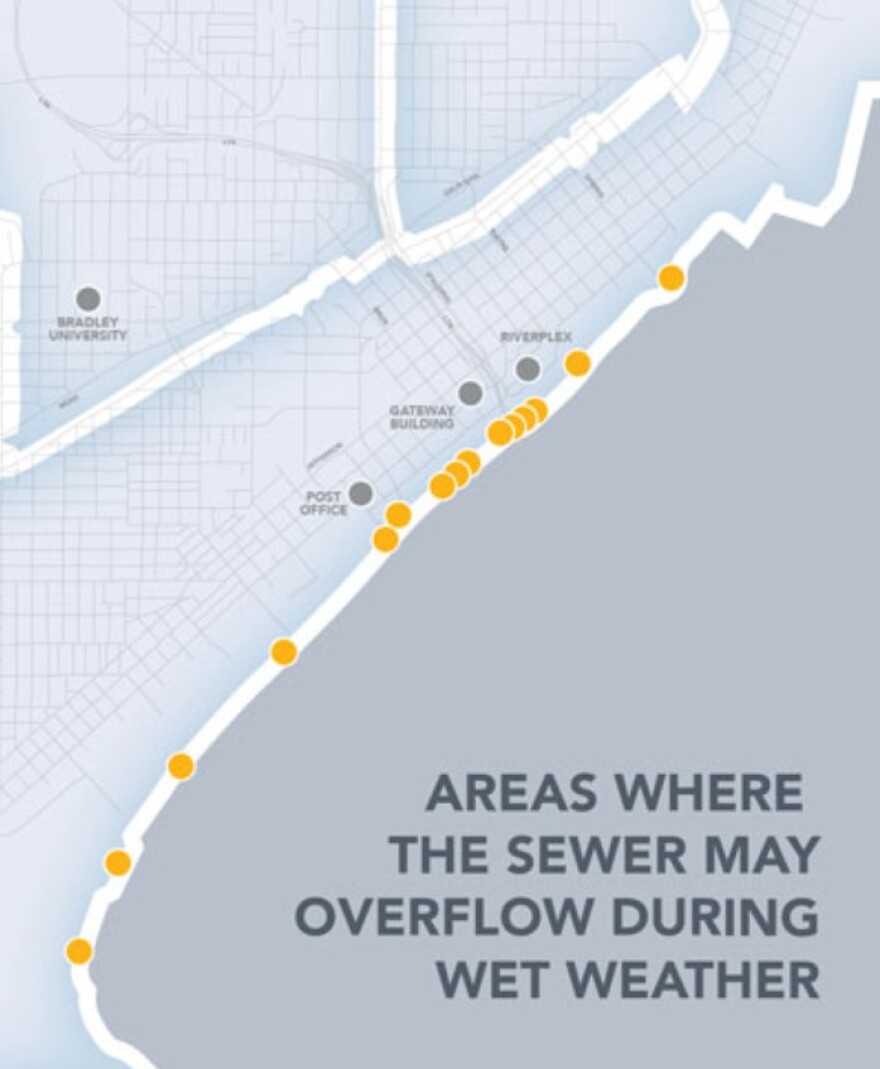

Andrea Klopfenstein: The combined sewer system is a system where we have storm sewer and sewage both flowing into the same pipe. So in dry weather, it's just the raw sewage from homes and businesses that goes to the wastewater treatment plant. But when it rains, the stormwater also gets into that same pipe with the raw sewage, and there's a lot of times too much water than the pipes can handle. So the pipes end up discharging that combined sewer overflow into the Illinois River.

What did the federal consent decree between the city and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency entail?

Klopfenstein: So it has a lot of very technical things, but the high level answer is: We need to reduce the number of CSO events that are occurring for a certain design storm. Every rainfall is different, so you can't really count the number per year because if you have really small rainfall events, you might have zero (and) if you have really big rainfall events, you might have more. So they set a certain design storm (threshold) that we have to meet.

There's probably not a simple way to explain it, but what are those standards that you have to meet?

Klopfenstein: Those are really complicated.

Well, then what is the overall timeline for correcting this problem?

Klopfenstein: Our long term control plan is an 18-year plan (and) 2022 is Year One. So we are just kicking off our first construction project this year and then we will go for 18 years with construction projects to meet the goals that we have to reduce the number of CSOs. Then there's monitoring that goes even past that 18 years, so this is really a long-term project for the city.

This has obviously been a problem for decades. Why did it take so long for an agreement to be reached so the work could get started?

Klopfenstein: We've had the CSOs since the late 1800s, early 1900s, so this has been a long process for our infrastructure. Way back when it was first built, it was state-of-the-art technology, and then over time we realized, (with) more people (and) more pollution, that it wasn't really an effective solution. But the city did a project in the late 1980s, and then we also got hit up by the EPA – and it was about 2007 – to look at it again and reduce the CSOs even further. So we've been negotiating with them for quite a while.

At one point, the target dollar figure was $500 million, and the city pushed back and said (that) it shouldn't be about affordability, which is what the EPA was saying: “Your community can afford to have a solution of $500 million,” (and) the city was saying, “We want you to give us metrics that we have to meet, not ‘the city can afford it, therefore you should spend it.’” So that was a lot of the round-and-round that went through the negotiations.

Also, the original solution was 100% “gray” – so it was going to be a tank or a tunnel that was just going to take all the water, store the water, wait until the storm passed and there was capacity, and then release that water slowly into the system so it could all be taken to the treatment plant. But that was very expensive; if you were doing a tunnel, it was only overseas contractors – there's only like four in the world that could have even built it.

So the city was trying to come up with a better way that would have more impact for our community. If you build a big tunnel, no one sees it except maybe the engineers, right? It’s underground, out of sight, out of mind, a big giant cost to it. So we started looking at green infrastructure.

Some of the benefits are you can do smaller, bite-sized projects; you can keep the money in the hands of local contractors. Local community members can be working on those projects with those contractors. So we get the benefit of job creation, we get the benefit of the infrastructure is now on the surface where people can see it. We can use it to connect communities, and we're hoping how the Year One project looks – where we have pavers going in one direction and bump-outs in the other – that it gives kind of like a redefining what the neighborhood will look like and give it a little bit more of something that you can see for your money, as compared to a tank or tunnel on the ground.

So the Year One project work, as I understand it, is already underway and it's using permeable pavers and bump-out planters along the roadways on the Near North side. Is that going to be the same plan in future years of the project?

Klopfenstein: So we have flexibility to determine what we want. So we're going to do the pavers and the bump-outs, and then monitor and see how that goes and evaluate performance, efforts for maintenance and community feedback. Then we'll use that information as we move forward to make adjustments to our plan.

Western Avenue (reconstruction) was another project that we did that's going to have significant CSO reduction. Unfortunately, that's a $14 million project and we don't have $14 million every year to do that level of effort. But we will take those opportunities that happen. So if we have another major arterial (road), like Main Street, when we get that money will probably have significant CSO impact. So the projects will be the same in that we're using green infrastructure (where) we're trying to remove the water from the pipes and soak it into the ground. But how it actually is accomplished might change, especially through this next 18 years.

Have you already mapped out target areas for future years of the project? Do you know yet where the year two year three work will be done?

Klopfenstein: So we're working south of MLK (Drive); there's a school over there (and) we're kind of in that general area just to give you kind of a landmark. That's what we're looking for Years Two and possibly Three. We will be working with our program manager and modeler to come up with a five-year plan to kind of identify those areas that's what we've talked about.

Again, one of the advantages of our plan is that we have flexibility to adjust and adapt. We’ve requested money from with the congressional directed spending request for Spring Street, so if that were to come through and be funded, we could shift to there, easily. The EPA is not requiring us to target certain areas; we're just targeting areas that makes sense within those sewer sheds.

How much will this entire project cost? Is it hard to estimate because each year may be different?

Klopfenstein: So when they did the long term control plan, which was signed in at the end of 2020, it was estimated to be $130 million in 2020 dollars.

I see. So how will this impact residents financially? Will it be reflected in tax increases or higher utility bills or anything along those lines?

Klopfenstein: The sewer rates will help cover some of that, and as we figure out the funding mechanism, (City) Council will need to weigh in on what needs to happen. If it's (increased) sewer rates, (or) some of the stormwater utility fee is used, (or) if there's a property tax increase, that is kind of still all up in the air and open for Council to weigh in and make those determinations.

But right now, for the Year One projects, the city received a low interest state revolving loan, which the money is, I think it's like 1% (interest). It's really low, so it's a really good idea for us to utilize that loan as much as possible, and that's what we've been directed to do at this point.

Another concern regarding the cost of the project, are you seeing expenses for materials escalate to a point where they're far exceeding original projections?

Klopfenstein: Yeah, it's changing – every time we bid, there's some new thing, right? If you remember back, plywood was the big thing that no one had within the past year. Now it's turned to metal products are the ones that we’re struggling with, so concrete pavements that have rebars in them and other metal are becoming more problematic. People, they can't get them; not only are they expensive, but they can't get them. So then the schedules get affected, and it just does a rolling effect: as you can't get materials, you can't meet your schedule.

As a community, we want our projects done in a reasonable timeframe. We can't just let materials roll in whatever. It's just been a whirlwind in trying to figure out – I mean, we have engineers working on updating cost estimates, but we come in and we're just like … every time you get a new bid, it's a new number for the same exact product that we've been doing for decades. It's very unusual times.

Is this also an issue with labor where there aren't enough crews to handle all the work that's needed?

Klopfenstein: So we're seeing it more impacted with contractors filling up and then not being able to bid on it, and I think that's because they don't have enough workers to staff the projects. So we see it kind of in a little different perspective, but we're definitely seeing less bidders on projects, or contractors are just telling us they're full for the year. So it's good, right? – that means we're getting a lot of work done and people are busy. But as more and more grant funding is rolling out, if our prices are twice as high and we can't get contractors to build it, we're kind of going to be in a pinch.