The city of Peoria derives its name from the Peoria Native American tribe — descendants of the mound civilization and members of the Illini confederation.

But until a few decades ago, many didn't know the Peoria tribe still existed.

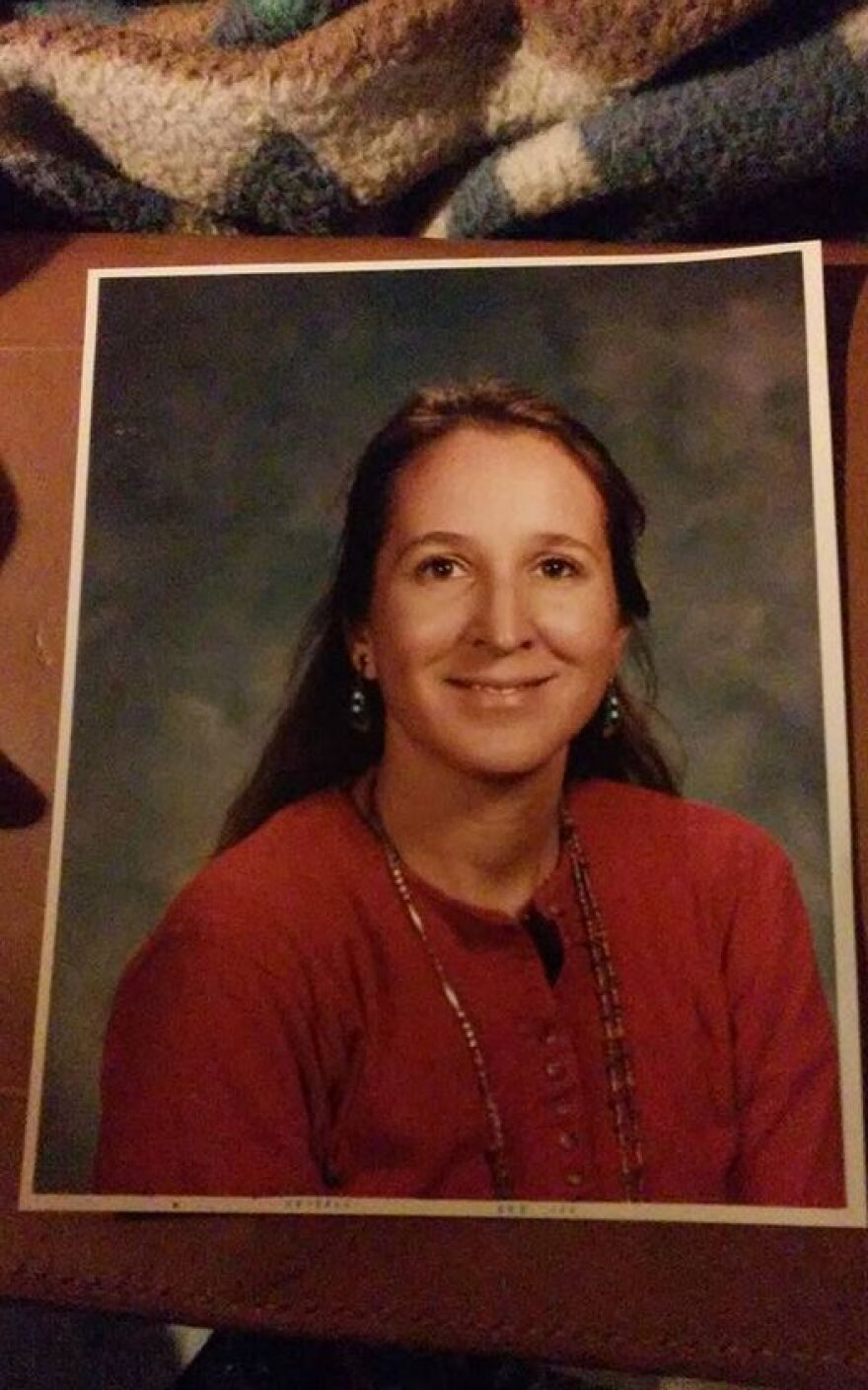

In a conversation with WCBU's Hannah Alani, Peorian Jo Lakota describes her experience driving to Oklahoma to find modern day members of the Peoria tribe. A member of the Lakota and Walla Walla tribes, Bradley University alumna and a former high school teacher, Lakota also discusses what Thanksgiving means to her.

The following is a transcript of an interview that aired during "All Things Peoria" on Tuesday, November 23. It has been edited for length and clarity.

Jo Lakota: I'm in my 70s. In two of my lifetimes, there were Native people living here. So this is not ancient history. You know, young kids today. They think the Vietnam War is an old thing. But the Indian people living here is not that old a thing. And for us, it was yesterday.

Hannah Alani: Can you tell us a bit about what you know about the Peoria tribe, and any tribes that lived here, and would still be here today, if not for the colonial expansion?

Jo Lakota: Well, I was living here when my kids were little, and I knew the lady that was the head of the library downtown. And she said, “We'd like to do a big program on Native Americans.” … And in doing that, I started asking about the Peoria Indians. And I was told repeatedly that they were … “They didn't exist anymore,” that they were “wiped out.” They had “lived down on the river, and they had been raided and murdered” … That “a few had gone up the river around Chillicothe … but that they had all been murdered.”

Well, then finally, there was a man that lived up in Lacon. And he said, “Oh, no, they live in Oklahoma.” Well, I had a $50 car. It was about ready to blow a gasket. But I put my two kids in the backseat, and we took off for Oklahoma to find them. And as it was, they were right over the border … into Oklahoma in a place called Miami, Oklahoma. And the Miami tribe, and the Peoria tribe, have Indian centers and everything there. So I found them.

Learn more: Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma

… But they always came back here. They are, they've always … They said, “We always go back. That's our home.” So they would come in groups and come and look at the river and see what was going on around here. Nobody would know they were coming. See, that still goes on. So this, they still think of this as their home.

Hannah Alani: And they had been coming back to Peoria, with no one here knowing, or noticing?

Jo Lakota: That’s right.

Hannah Alani: So what year was it that you went, and met them?

Jo Lakota: Oh, that would have been 40 years ago, or 45 years ago. Long time ago.

Hannah Alani: And how did things change, once people who lived in Peoria today realized that there was this tribe, still living, still coming back to the city to visit?

Jo Lakota: Well, actually the first year, we held the Return to Pimiteoui Powwow. It was called “Return,” and the Peoria people were the guests of the city of Peoria. And down there where the Mark Twain is, they gave them hotel rooms. And they took them on up, put them in a fancy bus and took them around, you know, up to Grandview Drive, and all the beautiful places here in Peoria. It’s a beautiful place we live in. I don't like it when people talk bad, because it is a beautiful place. I mean, I lived in New Mexico, the “Land of Enchantment.” So if I say Peoria is beautiful, I'm coming from a point of reference. … And they were well treated. And that – but that was one year – but they did come back, and other tribes came.

We actually have a Kickapoo family that lives in the area. We have a community here. We've had a drum here for 30 years, Eagle Ridge. Two of my sons are on that drum. We’ll go out to schools or libraries. We do this a lot, our group Eagle Ridge and Friends. And we have a dance troupe of over 20 people when we pull it together, people come from a great distance. We do huge programs at Summer Camp. We have a permaculture garden out there. … But we usually go to a distance for powwows, or actually to South Dakota or someplace like that for ceremonies. … We raised about $7,000 for Standing Rock here, with the help of Kenny's downtown, and different places.

…Then you go up by Bloomington, there's a little town called LeRoy. That was the Grand Village of the Kickapoo, and that was split into five tribes. They were an amazing people, as well. Of course, the Illini is a confederacy of tribes that all lived around here. Kaskaskia, Kickapoo, all of them.

The local farmers there got together and said … “Let's bring the Indians back.” So they went out looking, they were looking for the Oklahoma ones. And they knew that there were tribes in a few places. But they ended up finding five, and they actually sent a bus down into Mexico. So they, they brought that tribe up. And it was a miracle, because they still knew the old songs. They still dress that way, they still lived in the kind of homes they lived in here. And it was like going in a time machine for these other native people. It was a miracle.

Learn more: 1998 ‘Homecoming’ powwow at Grand Village in LeRoy

And I think the farmers and people there fed 3,000-4,000 people at that time. And they brought in all kinds of game and fruits and stuff, vegetables from their yard, gardens. And it was a big feast. It was wonderful. … And there was one woman who came, who was 100 years old, or more. And she remembered this big old tree that used to be there, and playing under it as a child, when it was her village. So this, this is not ancient history.

The Pantagraph: Powwow at Grand Village honors Kickapoo history

Hannah Alani: How do you think Thanksgiving should be taught in schools? How did you approach teaching this to students?

Jo Lakota: Well, there's a new book called Braiding Sweetgrass, written by a Potawatomi woman. Of course Potawatomi lived here. If you have a farm, it's probably Potawatomi homeland. If you've dug up arrowheads, and so forth. Many of them probably belong to those people. But Thanksgiving. What I see when I think of Thanksgiving is the great chief Philip, his head on a pole outside the European village there, after he had fed and clothed and nurtured these people. And when they realized he wasn't going to comply with everything they wanted, his head was on a pole. The people that came here were hungry and dirty. And I had someone really get angry me for one time for saying that, but they didn't … a lot of people in Europe didn't, in England particularly, were not into bathing. They thought it was unhealthy. So they came sick in that way. And the Indians took care of them.

But anyway, why I mentioned the book, Braiding Sweetgrass,” is because she gives there, in its pages, the prayer that you say daily, that Thanksgiving prayer. And they say it at the beginning of a meeting, because then everybody's on the same page. It's not majority rules. It's everybody thinking as one. So you start out, and you're thankful for the air. Then you're thankful for the earth that feeds us, the air that we breathe. And you're thankful for the animals. You're thankful for the trees that give us oxygen and shade and warmth. So it goes on and on and on. And by the end, everybody realizes, we are all one here.

Hannah Alani: How do you think [Thanksgiving] should be celebrated, if it should be celebrated at all?

Jo Lakota: To me, I celebrate Thanksgiving because I am terribly thankful. But I'm also very mindful. You know, it's like Columbus. He was a horrible, horrible person. And there are many great Italians. He wouldn't have gotten here, but for his Portuguese sailors. So, many great Portuguese. So why honor the one who sold children into slavery? Or chopped off people's hands because they didn't have gold in their island? Crazy things. He was insane. So, if you're not sorry about that, or if you're not sorry about slavery, and the unspeakable, horrific acts of slavery, or the genocide of native people, if you're not sorry for that, don't ever, ever be sorry about anything. It's horrible, things that happened. The way the Irish were treated when they came here. The Italians. The German and Japanese Americans, how they were treated, all that silliness. So Thanksgiving, it's, it's you know, it makes a cute little picture, doesn't it? But basically, they didn't … the white folk were not feeding the Indians. All they had in their hand was a Bible. They were starving to death. So that's what to be thankful for. The kindness of good people. And as my son always says, “That's the real brave people, are the kind people.” How brave are you? Can you be kind? Can you see what people around you need? That's being a warrior. That's being brave.

Hannah Alani: If there's something, one thing, that you'd like our listeners to kind of take away from this … a message to impart upon our Peoria community, what would you like that to be?

Jo Lakota: Mitakuye Oyasin. We are all related. Nobody is the other. No living thing is the other. So let us come together, at the same table, and give thanks for all that we have been given.

Hannah Alani: Wow, what language was that?

Jo Lakota: That's Lakota. I’m not fluent. But that's Lakota.

Hannah Alani: Your mother is part of the Walla Walla tribe and your father's Lakota. Can you tell me a bit about how your parents met, and how long your family was here in Peoria?

Jo Lakota: Well, my parents met while my father was in the service. And my mother was living in Urbana. ... They were living in Michigan, had a lot of native friends up there. I had grandpa, some relatives down here. And my dad, they came down here to work. ... We grew up in the Harrison Homes, but we were down at Kickapoo Creek all the time, in the woods. we had a good life. ... My dad was a bowmaker. We weren't hunters, but we would go down, and target practice down in the river bottoms. We'd have little straw targets. And we would forage down there. Used to be a lot of wild berries and asparagus and stuff down by the creek. ... We went to a little church, but we also knew our native religion, and we practiced that, and we were told not to discuss it at church or anywhere else, because people wouldn't understand.

...It's like, if you've gone to the ocean, and you're trying to describe what it's like to someone who's never seen the ocean. You can say it was beautiful, or it's a good thing, or it's wonderful. But you know, there's just a limit. Our culture is kind of that way, you know. It's hard to describe to people. It's something that has to be experienced, like a lot of things in life.

Hannah Alani: Tell me a bit more about the experiences you had growing up in Peoria that connected you to your culture.

Jo Lakota: My dad loved westerns, but we always rooted for the Indians, you know. We did a beadwork and leather work and made bows, made our arrows. On my 10th birthday, my parents had made me a teepee, we went down to Presleys worm ranch and got bamboo fishing poles for my teepee poles. It was a seven-foot diameter teepee. But, you know, we used it all the time. We just had semblances of our culture. And I was an avid reader. My parents took me to the library every week. ... We really didn't have money. But we spent lots of time outdoors. Loving the earth.

... I've got plenty of native ancestry. Also Shawnee and Cherokee in my family line. And I was adopted by a Pueblo family in New Mexico. So I know a lot about Pueblo people. I got to be in some inner circles. ... Blood quantum is something the Bureau of Indian Affairs came up with. People will ask you, "Well, how, how much Indian are you?" Well, that's something an Indian person will never ask you. They'll ask who your people are.

Follow Eagle Ridge and Friends on Facebook.

Follow the Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma on Facebook.